Participate in your Chapter! Attend a meeting and get involved.

Participate in your Chapter! Attend a meeting and get involved.

The Chapter Christmas party is December 19. Learn More>>

Newsletter content below: just click on a title bar to open the story.

- Americanism Elementary School Poster Contest

- The Joseph S. Rumbaugh Historical Oration Contest

- The George S. & Stella M. Knight Essay Contest

- ROTC/JROTC Recognition Program

- Massing of the Colors

- Arthur M. & Berdena King Eagle Scout Scholarship

- Tom & Betty Lawrence American History Teacher Award

CASSAR and NSSAR dues go to funding the many worthwhile projects of our Society. Have you read the NSSAR's Long-range Plan?

There are many project and activities you can become involved in. You just need to volunteer! Let's make this Chapter a leader in inspiring the community with the principles on which our nation was founded, maintaining and extending the institutions of American freedom, providing recognition for public service, supporting veterans and distributing an unbiased history curriculum.

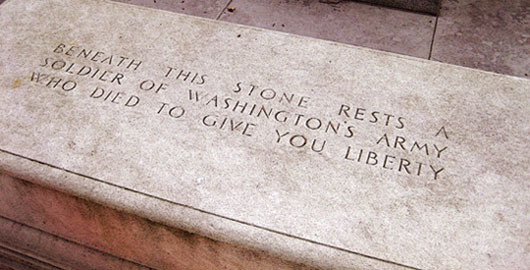

My wife and I recently visited Philadelphia, to take in the normal sights of interest to any SAR or DAR member. And while we were awed by Independence Hall, Carpenters's Hall, and Valley Forge, the most moving experience for me personally was time spent in reflection before the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier, a monument I was completely unaware of.

I highly recommend a visit to Philadelphia (in the cool spring or fall) and believe the following description, taken from ushistory.org, the Independence Hall Association's Web site, will inspire you to make the trip.

The Tomb lies within Washington Square, one of the five public parks drawn up by William Penn in his 1682 blueprint for Philadelphia. Shortly after the square was laid out, however, it was being used for a wholly other purpose — as a potter's field. Burials in Washington Square, then known as Southeast Square, started in 1706 and continued for nearly nine decades.

A letter of John Adams, dated the 13th April, 1777, captures the somber mood in the square: "I have spent an hour this morning in the Congregation of the dead. I took a walk into the 'Potter's Field,' a burying ground between the new stone prison and the hospital, and I never in my whole life was affected with so much melancholy. The graves of the soldiers, who have been buried, in this ground, from the hospital and bettering-house, during the course of last summer, fall and winter, dead of the small pox and camp diseases, are enough to make the heart of stone to melt away! The sexton told me that upwards of two thousand soldiers had been buried there, and by the appearance of the grave and trenches, it is most probable to me that he speaks within bounds. To what causes this plague is to be attributed, I don't know--disease had destroyed ten men for us where the sword of the enemy has killed one!"

By 1778, Washington Square would be the last barracks for the thousands of soldiers who died in Philadelphia. Though not much fighting occurred in Philadelphia during the War, plenty of dying did. Those wounded in nearby battles, or those sick with disease would be brought to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Hospital and the Bettering House for the Poor filled quickly. Churches became ad-hoc hospitals. And during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777, the Walnut Street Jail became a Dantesque vision of hell.

Historian Watson interviewed a survivor of the Walnut Street Jail some years after the War's end. The veteran, Jacob Ritter, recalled that prisoners were fed nothing for days on end and were regularly targets of beatings by the British guards. The prison was freezing as broken window panes allowed snow and cold to be the only blankets available to the captives. Ice, lice, and mice shared the cells. Desperate prisoners dined on grass roots, scraps of leather, and "pieces of a rotten pump." Rats were a delicacy. Upward of a dozen prisoners died daily. They were hauled across the street and slung in unmarked trenches like carcasses from an abattoir.

After the square stopped functioning as a cemetery, a beautifying campaign was undertaken. In 1825, the Square was renamed in honor of George Washington, commander of many of the troops buried within it.

In 1954, the Washington Square Planning Committee decided to erect a memorial that honored both George Washington and an unknown soldier from the Revolutionary War.

Various messages engraved on the wall of the memorial include: "Freedom is a light for which many men have died in darkness"; "The independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint councils and joint efforts of common dangers, suffering and success [Washington Farewell Address, Sept. 17, 1796]"; and "In unmarked graves within this square lie thousands of unknown soldiers of Washington's Army who died of wounds and sickness during the Revolutionary War."

The tomb of the Unknown Soldier itself bears the words: "Beneath this stone rests a soldier of Washington's army who died to give you liberty."

An eternal flame flickers in front of a wall bearing a replica of Jean Antoine Houdon's famous bronze sculpture of George Washington. Washington's eyes gaze eternally upon nearby Independence Hall.

You do know we have audio on our Web site, right? We have 26 audio titles in the Audio section of RevolutionaryWarArchives.org. These titles can be a great way to introduce young children to the Revolution in an interesting way before they become completely unreachable by anything but a computer game. And there are college-level lectures for us adults as well (did you know Benjamin Franklin discovered the Gulf Stream?). The only thing stopping us from adding more titles, is, you guessed it, member involvement. Contact the Webmaster to get involved.

About the time he began strategizing for higher office Theodore Roosevelt, an SAR Compatriot , wrote "Hero Tales from American History" with Henry Cabot Lodge to tell stories of heroic Americans. "Its purpose. . .is to tell in simple fashion the story of some Americans who showed that they knew how to live and how to die; who proved their truth by their endeavour; and who joined to the stern and manly qualities which are essential to the well-being of a masterful race the virtues of gentleness, of patriotism, and of lofty adherence to an ideal." A study of TR's papers reveals that he hoped to join the group of heroes he and Lodge celebrated in this monograph, originally published in 1895.

, wrote "Hero Tales from American History" with Henry Cabot Lodge to tell stories of heroic Americans. "Its purpose. . .is to tell in simple fashion the story of some Americans who showed that they knew how to live and how to die; who proved their truth by their endeavour; and who joined to the stern and manly qualities which are essential to the well-being of a masterful race the virtues of gentleness, of patriotism, and of lofty adherence to an ideal." A study of TR's papers reveals that he hoped to join the group of heroes he and Lodge celebrated in this monograph, originally published in 1895.

The Chapter needs your input! In viewing other SAR Chapter sites, I came across something that’s a great idea: publishing the biographies of the Chapter member’s Patriot Ancestors. This is not only of interest to the other Chapter members, it serves as an important resource to our cousins out there who are searching for their ancestors. What better way to honor the memory of those who sacrificed for our nation’s founding that to tell their story.

The reason I chose the illustration of a faceless patriot used for our web site is that most of us do n’t know what our ancestors looked like. Their features are lost to us. However, with a little work, we can all find out where they were and what their life was like at the time of the Revolution, based on contemporary accounts of the people around them. This brings them to life and makes the Revolution more real to all of us.

n’t know what our ancestors looked like. Their features are lost to us. However, with a little work, we can all find out where they were and what their life was like at the time of the Revolution, based on contemporary accounts of the people around them. This brings them to life and makes the Revolution more real to all of us.

So, I invite all Chapter members to submit a biography for each of their Patriot Ancestors. Each can be as long or as short as you like (that’s another advantage of the Web). You can use illustrations as well, but keep in mind the must be your own photos, or images in the public domain.

We already have some posted on our Web site, so take a look and get started on yours today!

To further the study of the American revolution, your webmaster is reviewing out-of-print texts to bring quality scholarship to you. Over the next months, I will publish a commentary on each battle of the Revolution in order of occurrence.

The author of each is Colonel Henry B. Carrington, MA, LLD, who wrote "Battles of the American Revolution 1775-1781." Published by AS Barnes & Company in 1876. The work is in the public domain, and not subject to copyright. He was professor of natural science and Greek at the Irving Institute in Tarrytown, New York, from 1846 to 1847. Under the influence of the school's founder, Washington Irving, he wrote "Battles of the American Revolution." Carrington subsequently became adjutant general for Ohio, mustering ten regiments of militia at the outbreak of the American Civil War and organizing the first twenty-six Ohio regiments. Learn more>>

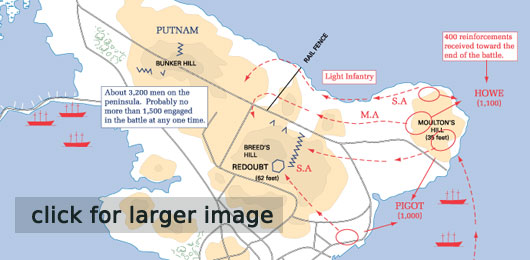

General Putnam  was very early at headquarters of the army at Cambridge, and urged that an additional force be sent to Charlestown Heights to reinforce Colonel Prescott's command. General Ward finally consented, so far as to order one-third of Colonel Stark's regiment to the front. The sequel will show that this was timely aid.

was very early at headquarters of the army at Cambridge, and urged that an additional force be sent to Charlestown Heights to reinforce Colonel Prescott's command. General Ward finally consented, so far as to order one-third of Colonel Stark's regiment to the front. The sequel will show that this was timely aid.

Major Brooks met General Putnam and pushed forward on his errand, while the general himself proceeded directly to the field of danger.

General Ward gave little heed to the urgent demand of Major Brooks, declining further to reduce his own force, lest the British garrison should make a movement upon Cambridge, and thus imperil the safety of accumulating stores, and even that of the entire army The committee of safety was in session. Richard Devons, one of its most valuable members, is credited with the influence which persuaded them to furnish additional reinforcements. Colonel Sweet states, that orders were also issued to recall from Chelsea the companies there stationed, in order to increase the force at headquarters.

The committee rested under a grave responsibility. "Their entire supply of powder, which could be obtained north of the Delaware, "according to Bancroft and other eminent authority, "was twenty-seven half barrels, and a present from Connecticut of thirty-six half-barrels more." Bancroft adds : "The army itself was composed of companies incomplete in numbers, enlisted chiefly within six weeks, commanded, many of them, by officers unfit, ignorant, and untried, gathered from separate colonies, and with no reciprocal subordination but from courtesy and opinion."

Fearful to waste ammunition, solemnly bound to have regard to the whole army and ultimate ends, as well as constrained to support the movement which they had themselves enjoined, it is not strange that calm deliberation foreran the decision of the committee when the appeal of Major Brooks was made.

It was therefore as late as eleven o'clock when the whole of the New Hampshire regiments of Stark and Reed were ordered to reinforce Prescott. This detachment reached its destination in time to participate in the action, although not until after the landing of the British troops.

Sweet credits the regiments of Colonels Brewer, Nixon, Woodbridge, and Major Moore, with a contribution of three hundred men each.

Frothingham shows conclusively that, "several of the companies of Little's regiment were elsewhere on duty, one at Gloucester, one at Ipswich, one at Lechmere's Point, and some at West Cambridge" ; but adds that, "Lunt's company arrived on the field near the close of the battle."

Bancroft carefully compiles from official reports and depositions, a statement, approximately as correct as can be derived from existing evidence, and thus states the force which hastened to the aid of Prescott: "Of Essex men, (Little's regiment) at least one hundred and twenty-five ; of Worcester and Middlesex men, (Brewer's) seventy or more, and with them, Lieutenant-colonel Buckminster; of the same men, (Nixon’s) fifty men, led by Nixon himself; forty men (Moore's) from Worcester; of Lancaster men, (Whitcomb's) at fifty privates, with no officer higher than captain.”

The hot day wore out its hours, as the tired troops resting from their assigned duty, panted for water, hungered for food, and waited for the enemy; and neither food nor reinforcements appeared in view, while the hostile forces were rapidly marshaling for attack.

The surrounding waters were salt sea water, or its brackish mixture with the flow from the Charles and Mystic rivers, and no fresh water was easy of access. A conviction that they were deserted began to spread through the ranks, that they had been pushed forward rashly, upon an ill-considered enterprise, and that there was wanting the disposition or nerve to undertake risks for their support or rescue.

It was at such a moment, terrible in its doubts and grand in its resolution, that Seth Pomeroy, then seventy years of age, having wisely declined his commission as Brigadier-general, found his way to the redoubt, musket in hand, to fight as a private volunteer.

And it was just then that Dr. Joseph Warren, President of the Provincial Congress, loved and honored of all, the undoubted patriot, and already monumental for worth and courage, added his presence and the beams of his animation to cheer the faltering and faint. He also declined command, served under Prescott, and plied his musket with the best when the crisis came on.

Ward himself, when the embarkation of the second British detachment furnished evidence that Cambridge was not in peril, hurried other troops toward the isthmus, but too late to avert the swift catastrophe.

Upon completion of the redoubt, it became painfully evident that the preliminary work was not yet complete. A new line of breastwork, a few rods in length, was hastily carried backward and a little to the left; and very hasty efforts were made to strengthen a short hedge, and establish a line of defense for a hundred-and-twenty rods in the same direction, thereby to connect with the stone fence and other protection which ran perpendicularly toward the Mystic river. This retreating line was begun under the personal direction of Prescott himself, but was never fully closed up. A piece of springy ground on this line was left uncovered by any shelter for troops acting in its rear, or passing to and fro behind the main lines. The stone fence, which took its course nearly to the river, was like those so common in New England at the present day. Posts are set into a wall two or three feet high, and these are connected with two rails, making the entire height about five feet.

Freshly mown hay which lay around in windrows or in heaps, was braided or thatched upon these rails, affording a show of shelter, while the top rail gave resting place for the weapon. In front of this, an ordinary zig-zag, "stake and rider " fence was established, and the space between the two was also filled with hay.

This line was nearly six hundred feet in rear of the front face of the redoubt, and near the foot of Bunker Hill. To its defense Prescott assigned Connecticut men under command of Captain Knowlton, supported by two field pieces on the right, adjoining the open space already mentioned.

Still beyond the rail fence eastward, towards the river, and extending by an even slope to its very margin, was another gap which exposed the entire command to a flanking movement of the enemy, endangering the redoubt itself, as well as the more transient works of defense. To anticipate such a movement, subsequently attempted, an imperfect stone wall was quickly thrown together by the assistance of Colonel Stark's detachment, whose timely arrival had cheered the spirits of the worn out pioneer command.

Meanwhile, Putnam was everywhere present to encourage the men, and superintended the establishment of light works on Bunker Hill summit, to cover the troops in case of forcible ejection from the advanced defenses. He caused the entrenching tools, no longer needed at the front, to be taken to that position. In spite of his entreaties and commands, some who thus carried the tools, threw them down upon reaching the summit, and took refuge behind the isthmus; others returned to their places at the front.

His movement, which would have been appreciated by well disciplined troops, carried with it the suggestion of a contingency which defeated its purpose in the hands of men not soldiers. Putnam's efforts accomplished nothing of value in the preparation of ulterior defenses. The time was too short, the control of men too feeble ; and the organization and discipline of the reinforcements which arrived, were too slack for their immediate subjection to authority, while the advancing enemy began to absorb the whole attention. Prescott's force at the redoubt had dropped off to less than eight hundred men when Colonel John Stark arrived. "Next to Prescott, he brought the largest number of men into the field," says Bancroft. The British were already landing, as they crossed the isthmus under a heavy fire. The execution of that movement was characteristic of their brave commander, and well calculated to impart the courage which afterward sustained his men. When Captain Dearborn, advised a quick step, he decided, that "one fresh man in an action was worth ten fatigued ones," and then deliberately advanced to his position.

As he descended the southern slope of Bunker Hill, his eye took in the whole plan of preparation for the battle. He saw, as he afterward related the affair, " The whole way so plain upon the beach along the Mystic river, that the enemy could not miss it." He went to work. Reed's regiment, which had been detailed with Starks' early in the morning, upon the importunity of Putnam, was at the rail fence with the Connecticut men. With every possible strain upon the New Hampshire men, this last obstruction was not sufficiently perfected to cover Starks' command, so that their ultimate defense was made while many were kneeling or lying down to deliver fire.

No other troops than those already named, arrived in time to take part in the action, and the total force which eventually participated in the battle did not exceed fourteen hundred men.

Six pieces of artillery were in partial use at different times, but with inconsiderable practical effect, and five of these were left on the field when the retreat was made.

The embarkation of the British troops was the signal for renewed activity of the fleet. The base of Breed's Hill, and the low ground extending to the river, was swept by a fire so hot, that no troops, if any had been disposable for such a movement, could have resisted the landing.

Perfect silence pervaded the American lines. A few ineffectual cannon shots were fired, the guns were soon taken to the rear, and a still deeper calm enveloped the hill. The day was intensely bright and hot. Barge after barge discharged its fully equipped soldiery, then returned for more.  This brilliant display of force, nowhere surpassed for splendor of outfit, precision of movement, gallant bearing, and perfect discipline, was spread out over Morton's Hill in well ordered lines of matchless array. With professional self-possession, these men took their noonday meal at leisure, while the barges returned for still another division.

This brilliant display of force, nowhere surpassed for splendor of outfit, precision of movement, gallant bearing, and perfect discipline, was spread out over Morton's Hill in well ordered lines of matchless array. With professional self-possession, these men took their noonday meal at leisure, while the barges returned for still another division.

Simultaneously with this reinforcement, the roar of artillery was heard from beyond Boston. As if to threaten General Ward, then at Cambridge, and General Thomas, who with several thousand Massachusetts men was then at Roxbury, and to warn both that they could spare no more troops for the support of Prescott; or, from the apprehension that an attempt might be made by the Americans to force an entrance to the city over Boston Neck, the batteries which covered the Neck opened forth a heavy fire of shot, shell and carcasses upon the village of Roxbury and its defenses. It was no less an indication to the silent yeomen on the hill, that mortal danger demanded a supreme resistance.

The crisis was at hand. The veterans were ready. The people were also ready.

The shaft of war, in the grasp of the trained legions of Great Britain was poised, and to be hurled at last upon the breasts of Englishmen, whose offense was the aspiration to perpetuate and develop the principles of English liberty.

It was a blow at Magna Charta itself, a home thrust, suicidal, and hopeless, except for evil! Its lesson rolls on to attend the march of the centuries.