A list of items of history, in no particular order.

Revolutionary War Widow’s Pension in 1906

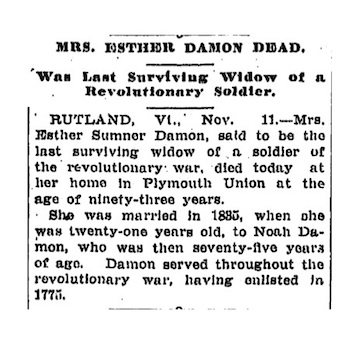

Did you know that the there was a Revolutionary War widow’s pension still active in 1906?

Esther Sumner (Damon) was 21 yrs. old in 1835 when she married 75 year old Revolutionary War veteran, Noah Damon, and was receiving a widows’ pension until she passed away in Nov. 1906.

The youngest Revolutionary War ancestor our Chapter represents is probably John Howard Jr. – Patriot ancestor of Wally Lauzon. John Howard was 14 yrs. old in 1782 when he acted a spy, eavesdropping on loyalists and Cherokee Indians, (John spoke Cherokee).

Battle of Freetown

On May 28, 1775, the Battle of Freetown was fought in a part of the town that is now part of the city of Fall River.

The Mount Hope Bay raids were a series of military raids conducted by British troops during the American Revolutionary War against communities on the shores of Mount Hope Bay on May 25 and 30, 1778. The towns of Bristol and Warren, Rhode Island were significantly damaged, and Freetown, Massachusetts (present-day Fall River) was also attacked, although its militia resisted British activities. The British destroyed military defenses in the area, including supplies that had been cached by the Continental Army in anticipation of an assault on British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island. Homes as well as municipal and religious buildings were also destroyed in the raids.

On May 25, 500 British and Hessian soldiers, under orders from General Sir Robert Pigot, the commander of the British garrison at Newport, Rhode Island, landed between Bristol and Warren, destroyed boats and other supplies, and plundered Bristol. Local resistance was minimal and ineffective in stopping the British activities. Five days later 100 soldiers descended on Freetown, where less damage was done because local defenders prevented the British from crossing a bridge.

(wikipedia article)

Battle of Kings Mountain

Reprinted by Permission from the SAR Magazine, Fall 2005.

Many historians consider the Battle of Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780 to be the turning point in America’s War for Independence. The victory of rebelling American Patriots over British Loyalist troops completely destroyed the left wing of Cornwallis’ army. This decisive battle successfully ended the British invasion into North Carolina and forced Lord Cornwallis to retreat from Charlotte into South Carolina to wait for reinforcements. This triumphant victory of the Overmountain Men allowed General Nathanael Greene the opportunity to reorganize the American Army.

Throughout the 225th anniversary year (2005) of this so very important event in America’s history, I wish to encourage us to remember and honor the “Heroes” of the Battle of Kings Mountain: all 1,400 or so men who took a stand against Patrick Ferguson and his troops of British Loyalists. I also want to commend Lyman P. Draper for all of his efforts accurately documenting so much of our nation’s history with writings from personal interviews of individuals “who were there” and to also say “thanks” for allowing me to borrow the title of his book for my exhibit of artifacts belonging to and in honor of, the men that fought heroically in this significant battle.

BY WAY OF BACKGROUND

Following the defeats of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln at Charleston in May and then Gen. Horatio Gates at Camden, British Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis appeared to have a clear path all the way to Virginia. In September, Cornwallis invaded North Carolina and ordered Major Patrick Ferguson to guard his left flank. On September 2, Ferguson left for Western Carolina with seventy of his American Volunteers and several hundred Tory soldiers. He arrived at Gilbert Town, North Carolina, on September 7th. Ferguson paroled a captured rebel and sent him with a message, “that if they did not desist from their opposition to the British arms, and take protection under his standard, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword. “

THIS THREAT PROVED TO BE HIS UNDOING!

A call to arms went out and they gathered at Sycamore Shoals. David Ramsey, in his history of South Carolina, written in 1808, said, “hitherto these mountaineers had only heard of war at a distance, and had been in peaceable possession of that independence for which their countrymen on the seacoast were contending. They embodied to check the invader of their own volition, without any requisition from the Governments of America or the officers of the Continental Army. Each man set out with a knapsack, blanket, and gun. All who could obtain horses were mounted, the remainder afoot. ” On Sept. 25th, Colonels William Campbell, Charles McDowell, John Sevier and Isaac Shelby left Sycamore Shoals in pursuit of Ferguson. The thoroughfare of their mission followed the only roadway connecting the backwater country with the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina.

Leaving Sycamore Shoals, the column marched up Gap Creek to its headwaters in Gap Creek Mountain, and there turned eastward and then south, following around the base of Fork Mountain to Toe River, and on up that stream to one of its tributaries. Here the route continued in a southerly direction until the top of the mountain was reached, between Roan High Knob and Big Yellow Mountain. From the mountaintop, descent was made along Roaring Creek to the North Toe River. It is stated in the diary of Ensign Robert Campbell that “the mountains were crossed and descent to the other side was carted before camp was made for the night. Snow was encountered in the highlands, for an elevation of 5,500 feet was reached in this march. On the top of the mountain there was found a hundred acres of beautiful tableland, and the troops were paraded, doubtless for the purpose of seeing how they were standing the march, which was about 26 miles to this point”. Campbell’s diary states that the second night, that of the 27th, they rested at “Cathey’s” plantation. Draper places this at the junction of Grassy Creek and North Toe River. Tradition has it that on reaching Gillespie Gap the troops divided, one group including Campbell’s men, moving southward to Turkey Cove, the other going easterly to the North Cove on the North Fork of the Catawba. Ensign Campbell’s diary gives the information that the fourth night, the 29th, Campbell’s men rested at a rich “Tory’s”, near Turkey Cove.

The following day the men who had camped at North Cove marched southeast down Paddy Creek, while those from Turkey Cove marched southerly down the North Fork and then hastily down the Catawba near the mouth of Paddy Creek. They continued down the Catawba to Quaker Meadows, the home place of the McDowells, and promptly made camp. During the five days that had elapsed since leaving Sycamore Flats, about 80 miles had been covered. On September 30th, Colonel Cleveland joined the marching column of 1,040 men at Quaker Meadow with the men from Wilkes County and Major Winston with the men from Surry County. An additional 30 Georgians, under the command of William Candler, joined the Patriot force at Gilberts Town, making for a combined strength of approximately 1,400 men.

CAMPBELL BECOMES COMMANDER

The seven Colonels chose Co!. William Campbell to act as overall commander. The Overmountain Men moved south in search of Major Patrick Ferguson. From the Rebel spy Joseph Kerr, they learned that Ferguson was thirty miles to the north, camped at Kings Mountain. It is said that Isaac Shelby was especially delighted to learn that Ferguson was quoted as saying, “He was on King’s Mountain, that he was King of that mountain and that God Almighty and all the Rebels of Hell could not drive him from it.” Shelby was very familiar with the Kings Mountain region and knew that it could prove to be an almost impossible position to defend.

The Colonels wanted to catch up with Ferguson before he reached Charlotte and Lt. General Charles Cornwallis’ protection, so they chose 900 of the best men and quickly made their way north. The combined force of Overmountain Men arrived at Kings Mountain the afternoon of October 7, 1780.

Having little insight into the methods and philosophies of warfare of the southern frontiersmen, Ferguson had chosen the position feeling no enemy could fire upon him without showing themselves. The Patriot force decided to surround the mountain and use continuous fire to slowly close in like an unavoidable noose.

The force was divided into four columns. Col. Isaac Shelby and Col. Wm. Campbell led the interior columns, with Shelby on the left and Campbell on the right. Colonel John Sevier led the right flanking column and Colonel Benjamin Cleveland the left. They moved into their respective positions and began moving toward the summit. The battle commenced at 3 o’clock with the middle two columns exchanging fire with Major Ferguson for fifteen minutes while the flanking columns moved into position. Ferguson used Provincial Corps to drive back Colonels Campbell and Shelby with a bayonet charge, but then his troops had to fall back from under sharpshooter fire.

Ferguson was right in believing that his attackers would expose themselves to musket fire if they attempted to scale the summit. But he did not realize that his men could only fire if they went into the open, rendering themselves vulnerable to returning rifle fire. Most all of the Patriot troops were skilled hunters, woodsmen and above all, “riflemen” who routinely killed fast moving animals to feed themselves. Most were veterans of many years of frontier Indians war and were experts on “tree to tree” no rules combat. On this day, Ferguson’s men would find escaping an impossible task.

Because of their exposed position, Major Ferguson’s men were being overwhelmed. The sharpshooters were picking them off from behind rocks, trees and brush that surrounded the summit; while the Loyalists’ aim was high, a common sighting problem when shooting downhill. The Overmountain Men gained a foothold on the summit, driving back the staggering Loyalists. The noose was quickly closing in. Major Ferguson’s bold and final attempt was to try and personally cut a path through the Patriot line so his forces might possibly escape, but this heroic effort failed as Ferguson fell from his horse, his body riddled with bullets. Some accounts say he died before he hit the ground; others say that his men propped him against a tree, where he died. Ferguson was the only British soldier killed in the battle, all others were Americans, either Loyalist or Patriot.

Ferguson’s second-in-command, Capt. Abraham DePevster, bravely continued to fight for a brief time, but the confusion was so great and his followers in such a vulnerable position that he realized further resistance was suicidal. He quickly raised the white flag of surrender. He surrendered his sword to Major Evan Shelby, Jr., younger brother of Kentucky’s first Governor Isaac Shelby. Gen. William Campbell was the commanding officer of the day, but it is said that he had removed his tattered coat “and with open collar”, not recognized as the commander. Despite the call for surrender by the Loyalists, the Patriot Colonels could not immediately stop their men from shooting. Many Patriots remembered that the notorious “Tarleton” had mowed down Patriot troops at Waxhaws despite the fact they were trying to surrender. But eventually…the fighting at Kings Mountain diminished.

AFTERMATH OF THE ENCOUNTER

The battle had lasted a little over an hour and not a single man of Ferguson’s force escaped. Though the number of casualties reported varies from source to source, some of the most commonly reported figures are that 225 Loyalists had been killed, 163 wounded and 716 were captured, while only 28 Patriots were killed, including Colonel James Williams, and 68 wounded. When General Cornwallis learned of Major Patrick Ferguson’s defeat, he retreated from Charlotte, North Carolina back to Winnsborough, South Carolina.

Historians agree that the Battle of Kings Mountain was the “beginning of the end” of British rule in its former colonies. In less than one hour of battle, the Overmountain Men not only captured the day but also undermined the British strategy for keeping America under its control. A defeat so crushing as that suffered by Major Patrick Ferguson is rare in any war. Although skewed, his position on Kings Mountain was thoughtfully selected using much experience and consideration. The plateau of the mountain was just large enough to serve as a battleground for his command and to provide space for his camp and wagon train. Water was near and plentiful. The slopes of the mountain would hinder the advance of the attackers. When attacked he expected that any retreat would be rendered perilous by flanking or encircling detachments, a condition he desired as his militia would be put to the task to stand and fight instead of having the choice to flee. From Patrick Ferguson’s point of view, a better position on which to take a stand could not have been found.

It can be assumed without a shred of doubt that Patrick Ferguson utterly underestimated the courage of the mountain men. Their apparent advantage in numbers did not discourage him from offering battle; otherwise he would have continued his march on October 7th in the direction of Charlotte and Cornwallis. But had he known that these Overmountain Men would so aggressively stand and fight with a fierceness and conviction never before experienced in his southern campaign, I’m sure he would have been much more cautious and considerably less heroic.

Battle of Lexington / Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. They were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy (present-day Arlington), and Cambridge, near Boston. The battles marked the outbreak of open armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen of its colonies on the mainland of British America.

In late 1774 the Suffolk Resolves were adopted to resist the enforcement of the alterations made to the Massachusetts colonial government by the British parliament following the Boston Tea Party. An illegal Patriot shadow government known as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was subsequently formed and called for local militias to begin training for possible hostilities. The rebel government exercised effective control of the colony outside of British-controlled Boston. In response, the British government in February 1775 declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. About 700 British Army regulars in Boston, under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, were given secret orders to capture and destroy rebel military supplies that were reportedly stored by the Massachusetts militia at Concord. Through effective intelligence gathering, Patriot colonials had received word weeks before the expedition that their supplies might be at risk and had moved most of them to other locations. They also received details about British plans on the night before the battle and were able to rapidly notify the area militias of the British expedition.

The first shots were fired just as the sun was rising at Lexington. The militia were outnumbered and fell back, and the regulars proceeded on to Concord, where they searched for the supplies. At the North Bridge in Concord, approximately 500 militiamen engaged three companies of the King’s troops at about an hour before Noon, resulting in casualties on both sides. The outnumbered regulars fell back from the bridge and rejoined the main body of British forces in Concord.

Having completed their search for military supplies, the British forces began their return march to Boston. More militiamen continued to arrive from neighboring towns, and not long after, gunfire erupted again between the two sides and continued throughout the day as the regulars marched back towards Boston. Upon returning to Lexington, Lt. Col. Smith’s expedition was rescued by reinforcements under Brigadier General Hugh Percy a future duke (of Northumberland, known as Earl Percy). The combined force, now of about 1,700 men, marched back to Boston under heavy fire in a tactical withdrawal and eventually reached the safety of Charlestown. The accumulated militias blockaded the narrow land accesses to Charlestown and Boston, starting the Siege of Boston.

Wikipedia Article

Battle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth was an American Revolutionary War (or American War of Independence) battle fought on June 28, 1778 in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The Continental Army under General George Washington attacked the rear of the British Army column commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton as they left Monmouth Court House (modern Freehold Borough). It is known as the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse.

Unsteady handling of lead Continental elements by Major General Charles Lee had allowed British rearguard commander Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis to seize the initiative, but Washington’s timely arrival on the battlefield rallied the Americans along a hilltop hedgerow. Sensing the opportunity to smash the Continentals, Cornwallis pressed his attack and captured the hedgerow in stifling heat. Washington consolidated his troops in a new line on heights behind marshy ground, used his artillery to fix the British in their positions, then brought up a four-gun battery under Major General Nathanael Greene on nearby Combs Hill to enfilade the British line, requiring Cornwallis to withdraw. Finally, Washington tried to hit the exhausted British rear guard on both flanks, but darkness forced the end of the engagement. Both armies held the field, but the British commanding general Clinton withdrew undetected at midnight to resume his army’s march to New York City.

While Cornwallis protected the main British column from any further American attack, Washington had fought his opponent to a standstill after a pitched and prolonged engagement; the first time that Washington’s army had achieved such a result. The battle demonstrated the growing effectiveness of the Continental Army after its six month encampment at Valley Forge, where constant drilling under officers such as Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben and Major General Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette greatly improved army discipline and morale. The battle improved the military reputations of Washington, Lafayette and Anthony Wayne but ended the career of Charles Lee, who would face court martial at Englishtown for his failures on the day. According to some accounts, an American soldier’s wife, Mary Hays, brought water to thirsty soldiers in the June heat, and became one of several women associated with the legend of Molly Pitcher.

(wikipedia article)

Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American army of General George Washington and the British army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777. The British defeated the Americans and forced them to withdraw toward the American capital of Philadelphia. The engagement occurred near Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania during Howe’s campaign to take Philadelphia.

Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the early stages of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after the adjacent Bunker Hill, which was peripherally involved in the battle, and was the original objective of both the colonial and British troops, though the vast majority of combat took place on Breed’s Hill.

On June 13, 1775, the leaders of the colonial forces besieging Boston learned that the British were planning to send troops out from the city to fortify the unoccupied hills surrounding the city, giving them control of Boston Harbor. In response, 1,200 colonial troops under the command of William Prescott stealthily occupied Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill. The colonists constructed a strong redoubt on Breed’s Hill, as well as smaller fortified lines across the Charlestown Peninsula.

When the British were alerted to the presence of colonial forces on the Peninsula, they mounted an attack against them. After two assaults on the colonial positions were repulsed with significant British casualties, the third and final attack carried the redoubt after the defenders ran out of ammunition. The colonists retreated to Cambridge over Bunker Hill, leaving the British in control of the Peninsula.

While the result was a victory for the British, the massive losses they encumbered discouraged them from any further sorties against the siege lines; 226 men were killed with over 800 wounded, including a large number of officers. The battle at the time was considered to be a colonial defeat; however, the losses suffered by the British troops gave encouragement to the colonies, demonstrating that inexperienced militiamen were able to stand up to regular army troops in a pitched battle.

wikipedia article

Howe’s army sailed from New York City and landed near Elkton, Maryland in northern Chesapeake Bay. Marching north, the British Army brushed aside American light forces in a few skirmishes. Washington offered battle with his army posted behind Brandywine Creek. While part of his army demonstrated in front of Chadds Ford, Howe took the bulk of his troops on a long march that crossed the Brandywine beyond Washington’s right flank. Due to poor scouting, the Americans did not detect Howe’s column until it reached a position in rear of their right flank. Belatedly, three divisions were shifted to block the British flanking force near a Quaker meeting house.

After a stiff fight, Howe’s wing broke through the newly formed American right wing which was deployed on several hills. At this point Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen attacked Chadds Ford and crumpled the American left wing. As Washington’s army streamed away in retreat, he brought up elements of Nathanael Greene’s division which held off Howe’s column long enough for his army to escape to the northeast. The defeat and subsequent maneuvers left Philadelphia vulnerable. The British captured the city on September 26, beginning an occupation that would last until June 1778.

Wikipedia article

Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton, New Jersey was one of the turning points of the American Revolutionary War. Having lost New York to the British at the Battle of Long Island in the summer, George Washington was desperate to turn things around.

After a long march through the snow, Washington led his troops across the partially frozen Delaware river on Christmas Day of 1776 to defeat the Hessian mercenaries and restore the fortunes of the American patriots. The army had lost two men to the Delaware River, and they had wet almost all their gun powder. It had been hard keeping the supplies from washing down the river; it was even harder having to march in the snow and risk frostbitten limbs. They were after the Hessian forces in Trenton, New Jersey. Their leaders, commander-in-chief George Washington, Major General Nathanael Greene, and Major General John Sullivan pushed them on with incredible courage.

The only way to get to Trenton without being detected by the British was by boat down the Delaware River. He had not chosen the best time of year to do this. Winter had begun, and crossing the Delaware was a risky venture. The river itself already had ice floes forming on its surface. Washington needed extreme courage to overcome the heavy spirit of the men, the forces of nature, and discovery by the British.

The plan was to cross the Delaware at three points: one with a Rhode Island regiment accompanied by Pennsylvania and Delaware troops, a second under Brig. Gen. Ewing, and a third led by Washington himself along with Major Generals Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan. Washington rode in front of his men as they marched down Pennington Road, about one mile northwest of Trenton. He sent out an advance of troops to a Hessian outpost in a copper shop on Pennington Road.

The battle began when a German, Lieutenant Andreas von Wiederholdt, came out of the copper shop to get fresh air and was shot at by the American troops. Some of his men ran from the shop and surrounding area when Lt. Wiederholdt started yelling, “Der Feind!” (The enemy!). The small contingent was no match for the American troops, and they hurriedly organized a retreat.

Washington knew that he needed to cut off all means of retreat for the Hessians. He ordered some of his men to disband and assemble near Princeton. General Sullivan stationed his men near Assunpink Creek. Some Prussians, Lt. von Grothausen and his Jägers [hunters], started to shoot at the Americans assembling near the creek, but they did not see all the troops that were advancing. Once they did, they beat a hasty retreat as well. Some of the German soldiers tried to swim across the creek while others fled across the bridge, which had not yet been taken by the colonist forces.

Other Hessian forces had heard the first shots being fired at the Americans and began to regroup along the major streets in Trenton to overpower them. They were professional soldiers, and the Americans mere farmers who had already lost New York.

When the Americans boldly met them head on, the Hessians realized they had miscalculated and began withdrawing their troops. They tried to flank Washington’s men north of the town. While Col. Rall and his men concentrated on Washington’s men, Sullivan and Greene split up their militia once more to block off escape routes from Trenton. Other colonist soldiers hid in the buildings and homes of civilians, hoping to be able to snatch any unfortunate Hessians who tried to escape.

Rall had now turned his attention elsewhere and, seeing that the colonists had taken control over their cannon, tried to fight to get it back. He was successful but to no avail. When they tried to turn four guns on the Americans, they found that the guns themselves would not fire at all. Forced once again to flee, they made for an orchard near the creek Gen. Sullivan and his men had been guarding. The Hessians were no match for the Americans this time. Sullivan’s troops began firing, and Rall was mortally wounded in the process. When their colonel was shot, the Hessian troops began to scatter in all directions. When Sullivan was joined by Washington not much later, the Hessians surrendered.

(Courtesy of revolutionary-war.net)

Battles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne led a large invasion army up the Champlain Valley from Canada, hoping to meet a similar force marching northward from New York City; the southern force never arrived, and Burgoyne was surrounded by American forces in upstate New York. Burgoyne fought two small battles to break out. They took place eighteen days apart on the same ground, 9 miles (14 km) south of Saratoga, New York. They both failed.

Trapped by superior American forces, with no relief in sight, Burgoyne surrendered his entire army on October 17. His surrender, says historian Edmund Morgan, “was a great turning point of the war, because it won for Americans the foreign assistance which was the last element needed for victory. Burgoyne’s strategy to divide New England from the southern colonies had started well, but slowed due to logistical problems. He won a small tactical victory over General Horatio Gates and the Continental Army in the September 19 Battle of Freeman’s Farm at the cost of significant casualties. His gains were erased when he again attacked the Americans in the October 7 Battle of Bemis Heights and the Americans captured a portion of the British defenses. Burgoyne was therefore compelled to retreat, and his army was surrounded by the much larger American force at Saratoga, forcing him to surrender on October 17.

News of Burgoyne’s surrender was instrumental in formally bringing France into the war as an American ally, although it had previously given supplies, ammunition and guns, notably the de Valliere cannon, which played an important role in Saratoga. This battle also resulted in Spain joining France in the war against Britain. The first battle, on September 19, began when Burgoyne moved some of his troops in an attempt to flank the entrenched American position on Bemis Heights. Benedict Arnold, anticipating the maneuver, placed significant forces in his way. While Burgoyne did gain control of Freeman’s Farm, it came at the cost of significant casualties. Skirmishing continued in the days following the battle, while Burgoyne waited in the hope that reinforcements would arrive from New York City. Militia forces continued to arrive, swelling the size of the American army. Disputes within the American camp led Gates to strip Arnold of his command. British General Sir Henry Clinton, moving up from New York City, attempted to divert American attention by capturing two forts in the Hudson River highlands on October 6; his efforts were too late to help Burgoyne. Burgoyne attacked Bemis Heights again on October 7 after it became apparent he would not receive relieving aid in time. In heavy fighting, marked by Arnold’s spirited rallying of the American troops, Burgoyne’s forces were thrown back to the positions they held before the September 19 battle and the Americans captured a portion of the entrenched British defenses.

(wikipedia article)

Battle of Saratoga (add’l)

Known as the turning point of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Saratoga was fought on September 19th and October 7th in 1777. Its two battles are also known as the Battle of Freeman’s Farm and the Battle of Bemis Heights, from where they took place, in upstate New York near Saratoga.

In September of 1777, the British were in control of New York, Rhode Island, and Canada. Native Americans and Germans had decided to side with the British. General Howe was about to take Philadelphia, the self-proclaimed capital of the new United States of America.

The march of British General John Burgoyne down the Hudson River and General Henry Clinton up the Hudson River seemed to spell the end of the American resistance.

This seemed all the more certain when General Burgoyne began his march by easily capturing Fort Ticonderoga.

General John Burgoyne’s plan was to march from Canada, down the Hudson river, and to capture Albany. With the British already in control of New York, Burgoyne figured it would be child’s play to take the Hudson river valley between the two cities once Albany was secured.

He and his forces capture Ft. Ticonderoga without a problem, but the journey through the Hudson river valley proved more difficult than expected.

The slow going was not the only problem. Gen. Burgoyne sent troops to Vermont to procure supplies and cattle, but they were attacked and defeated, costing Burgoyne a thousand men. A contingent of Native Americans decided to return home, lessening his numbers even more. And on top of all that, General Lincoln, a Virginian patriot, had gathered a group of men ranging to 750 people went to fight the British from the back. By picking off the British ranks from behind trees, they weakened Burgoyne’s army considerably.

The problems gave the American army time to set up defenses on the river at Bemis Heights, south of Saratoga.

The First Battle of Saratoga at Freeman’s Farm

The British were dependent on the river to transport supplies, but with Lincoln behind and patriot fortifications and cannons ahead, Burgoyne tried to slip a detachment of soldiers inland. There, at the farm of one John Freeman (a Loyalist, supporting the British), they ran into American troops under the control of General Horatio Gates.

Officially, the Battle at Freeman’s farm—the first battle of Saratoga—was a victory for the British. Despite being held to a standstill and being picked off by American sharpshooters, they eventually drove the Americans from the battlefield with the help of German reinforcements that arrived during cthe day.

However, during the battle on Freeman’s Farm, Burgoyne lost two men to each rebel.

Still hoping for reinforcements from General Howe in New York, Burgoyne decided to set up camp and hold what he had gained. The patriots, driven from the battlefield once already, let him do so.

But the British would not get their reinforcements.

The Second Battle of Saratoga at Bemis Heights

By October 3, General Burgoyne realized that General Clinton would never arrive in time. He was already forced to put his men on limited rations, and he did not want to surrender to the Americans, whom he considered almost conquered.

He decided on a rush on the patriots’ left flank, which he performed on October 7.

It was hopeless. While Burgoyne was losing men to American sharpshooters, the Americans had been joined by General Lincoln’s forces plus a steady stream of militia men. They easily withheld the British attack, and they almost killed General Burgoyne, shooting his horse, his hat, and his waistcoat.

Driven back, the British trooped gathered behind a couple redoubts (temporary fortifications), which were held nobly until an unexpected participant roared into the midst of the battle.

General Benedict Arnold at the Battles of Saratoga

Before Benedict Arnold was a traitor, he was a loyal American, and nowhere was he more effective than at the Battle of Saratoga.

General Arnold led much of the first battle at Freeman’s farm, but bickering with General Gates led to his being relieved of command between battles.

Once the battle was engaged, however, Arnold could not restrain himself, despite the fact that Gates had confined him to his tent. Riding wildly into the battle—to this day it is rumored that he was drinking—he led the attack on the British redoubts, broke the line of Canadian forces between them, and opened an attack on the rear of the redoubts by American troops.

As the redoubt was taken, Arnold was shot, breaking his leg. He was finally retrieved by the officer Gates had sent after him and returned to camp on a stretcher.

Darkness fell, and General Burgoyne led his beleaguered troops in flight back to Saratoga.

As a result of the American victory, the French gained enough confidence to begin to support the Americans militarily. They had already provided supplies, but now they would supply soldiers and join the patriot army in resisting the English.

Spain, too, decided to assist the war on the American side.

(Courtesy of revolutionary-war.net)